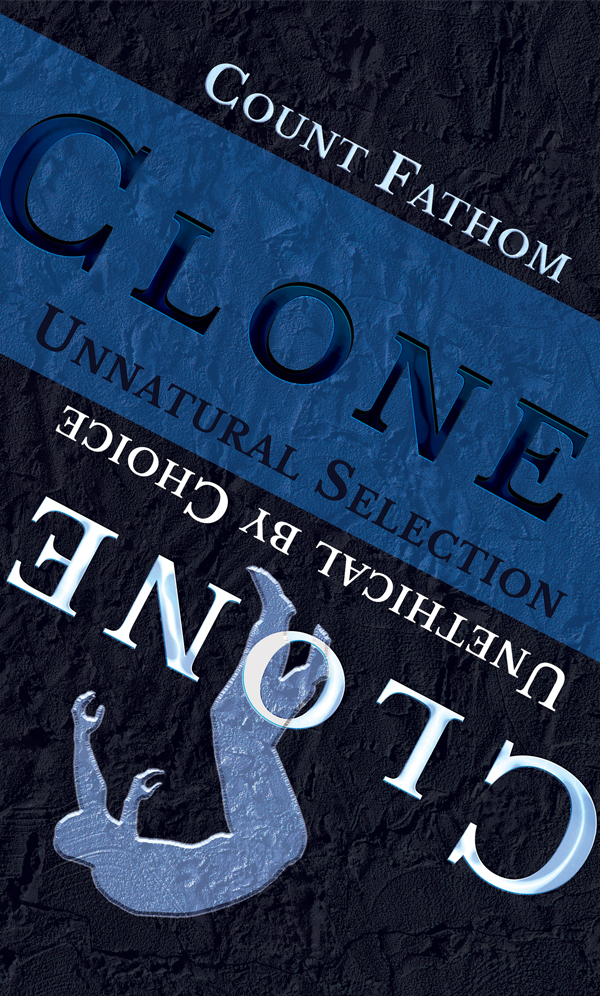

Unlucky by Nature… Unethical by Choice

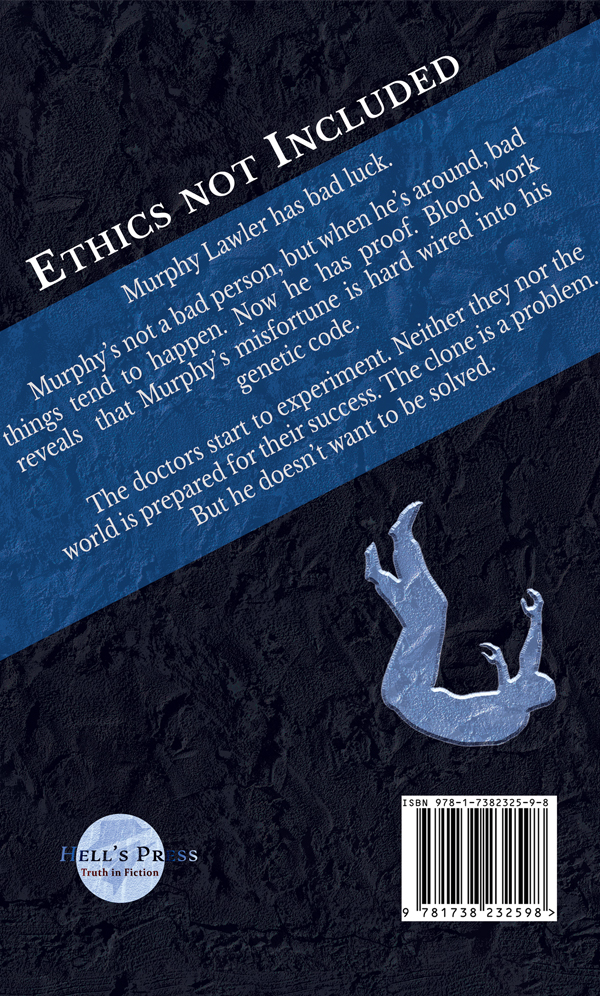

Murphy Lawler has bad luck.

Murphy’s not a bad person, but when he’s around, bad things tend to happen. When blood work reveals that Murphy’s misfortune is genetically hard wired, Murphy’s DNA becomes a valuable commodity to the scientific community. Murphy Lawler signs up for life as a lab rat.

Life doesn’t get any better for Murphy, but it couldn’t get any worse. He doesn’t care what they do with his genetic instructions.

Forging ahead with their experiments, the doctors accidentally create a Murphy clone. But the clone is not an exact copy of the original. The doctors changed Murphy’s code. The clone is not unlucky. He’s immoral.

The clone is a problem. But he doesn’t want to be solved.

Gwen has Barney stand in front of the fireplace this time. “Let me see it again.” He was standing behind the kitchen counter before, which was okay. The counter acted as a dais, but Gwen wants to see his posture without the counter as a crutch. Barney tries to do it right this time, but Gwen shakes her head. The silly goof can’t wave right. He looks absurd. The incumbent mayor is an excellent waver. They’re going to work on this until Barney doesn’t look the fool.

“I’m doing it just the way you told me.” Barney pleads.

“No, you’re not. You look like you have a neurodegenerative disorder. And you stand like a toddler with a balloon. You don’t look like a leader. You look like you’ll be picked last in a game of dodgeball. We have a lot of work to do before the election. We have three events planned. Maybe we’ll let your father wave, and you can just stand beside him.” Barney looks bummed out. She’s been picking on him for weeks. Gwen knows she’s being a little hard on him, but second place gets them nothing. Still, she doesn’t want to shatter his confidence. It’s Barney’s best attribute. “You’re smile is really charming. You’re doing that great.”

If Barney had a tail, it would wag. He latches on to the scraps of praise he’s offered. It’s easy to keep his spirits up. Gwen thinks she’ll have him ready when he needs to be. “Okay. Take the book down off your head. Let’s sit and discuss policy.”

Barney puts the book back on the shelf and runs his fingers through his hair. He’s gotten good at balancing it on his head. That was half an hour, and he didn’t touch it once. He sinks into the leather at the far end from Gwen. “First question. Immigrants are filling up our streets. Old ladies are afraid to walk to the grocers. Mother’s won’t let their children wander farther than arms reach. What are we going to do about this?”

Barney thinks he knows this one. “Immigrants are an important part of our electorate. We’ve got to do a balancing act, publicly acknowledging immigrants as appreciated by the government, while on the other hand we under fund, over police, and socially stigmatize their communities.”

Gwen’s face coils. She lunges like a mother rodent protecting her nest. Barney flinches, closing his eyes and snapping his head back. Both of their reactions are adaptations to habitual environmental pressures. But they have matured. Gwen doesn’t touch him. She restrains her instinct. Barney smiles. He was sure she wouldn’t hurt him. The adults in them have bloomed. Aawww.

“What are you going to tell the people, Barney, into a microphone.” Gwen straightens her hair and shakes like a dog.

“Don’t let a few rotten apples let you think the whole barrel is spoiled. Play it down, fend off the questions, keep the conversation moving with broad, trite phrases on diversity and equality.” Barney’s smile is bright and toothy. He’s learned that lesson. She taught it well, it’s stuck to the inside of Barney’s head.

Gwen is impressed, and gives his head a shaggy rub. It’s only rehearsal. “Good boy, Barney. Let’s try fiscal policy.”

“I have an idea. I want to share. I think I’ve got the hang of this.”

“Your own idea, Barney?”

“Yes, my own. I think I understand what you want.”

“Okay. Let’s hear it.”

“I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce all fidelity to any foreign prince, state, or sovereignty to whom I have heretofore been a subject. I will support and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic. I will bear true faith and allegiance to the country, and I am willing to heed a call to arms on her behalf. I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation, or purpose of evasion, so help me God.”

Sonya fills out the form, pays the fee , receives a stamped receipt, and is instructed that she must return to collect her citizenship documents within seventy two hours upon notification. Many tears of gratitude are shed in this room, but none today. Sonya is emotionally strong when she’s not bleeding. She’s excited though. She keeps it tight inside her chest until Tig and her get in the wagon, still chugging along after all their children.

Sonya begins a loud, sustained, merry howl. Tig harmonizes a fifth below. Sonya modulates her pitch and Tig follows in a vocal tango. Tig drums the steering wheel. Sonya thumps up at the ceiling. Tig lays on the horn. That’s a bit much. The few comers and goers in the parking lot dart sharp annoyed glances at them. Exuberance is replaced with laughter in the wagon.

“Let’s go buy a gun.” Sonya’s eyes are wide.

“We’ve never had a gun.” The question catches Tig off guard, but the joy of the day is too grand. His happiness will not be eclipsed.

“Because I wasn’t allowed. Some of my friends have them in Colombia. Loonies have guns. I want to protect myself from the loonies.”

“You think guns are cool, don’t you?”

Sonya admits. “Yes. Guns are cool. So cool.”

“If owning a gun helped protect you, then insurance companies would offer a discount for having one. The opposite is true.”

“We don’t own a home. But now we have a damn fine window. And we can have a gun. Life is grand, mi amor.”

“Let’s talk about gun ownership later. How about we go file a complaint with our local political representative. The lights in the street are too bright. They disturb my sleep. Or the water pressure could be better. Let’s threaten that bastard with legal action.” Tig has a citizen’s heart, but not their guts. Or self entitlement. His wife has enough for both of them.

Sonya has a new concern. “How can I differentiate myself from the undocumented immigrants, so that the police know to treat me right?”

Tig blushes at Sonya’s naivete. “Oh, baby, that’s not going to happen. We’re brown.”

Sonya is confused, and a little angry. “Even brown police?”

“Especially brown police.” Tig’s smile hints at a sadness hidden within.

“It’s all these illegals giving us a bad name.” By popular opinion all brown skinned people are lumped together in the same criminal basket. Sonya is upset. “I’m going to quit my job. I don’t want to help immigrants. I want to keep them out.”

Tig is surprised again. “But we’re democrats.”

“Not any more. I want a gun. Build a wall.” Sonya’s conversion is astounding. She has intuitively grasped the essence of the economic axiom, value in scarcity. “They’re ruining this great country. How long will it take to bring my family over?”

“How many are you thinking?”

“Mum and dad. My sister, but not my brother yet. Maybe when he gets out of debt and prison. We don’t want that trouble following us here. Aunt Isabella and Uncle Juan. Their three kids. Aunt Lucia and Uncle Pablo. Their four kids. Oh, why not all six aunts and eight uncles. Will there be a problem with the divorced ones? Oh well, we’ll get as many as we can. I hope there isn’t an age restriction. My grandparents are pretty old. I have some cousins that will do very well here. Law enforcement from the two countries don’t cooperate, do they? I’d hate to think any of them would be prejudiced against for joining the armed revolution. Or the drug convictions.” Sonya is thinking fast and speaking faster.

“Let’s look into the paperwork.” Sonya’s citizenship, and the window in their apartment, Tig has never been so happy. All of Sonya’s obstacles strike him as minor administrative toll bridges, lightly guarded and easily traversed.

“I think I should get a tattoo of the flag. Somewhere prominent. Then the police will know.”

“It won’t help.”

“It will. I heard Immigration and Customs Enforcement is hiring. Do you know where the building is? Maybe we can pick up an application on the way home. There’s sure to be a gun shop close by too.”

Their silence draws in the curiosity of others. The shake of the placards stills. The edge in their screams is dulled. The squint of their anger subsides. Their eyes grow wide as saucers at the miracle before them. More and more people pack into a room, a room one would think large enough to hold any number.

The people marvel. Pork belly, the fat rendered translucent, but finished at a high temperature so the fat is a bit crunchy on the outside. With just a look the people can taste that fat melting in their mouths. No one who can cook like that would salt the meat wrong.

Fish fillets in a tarragon cream sauce, a variation on a veloute. Clearly the fish had been pan fried first. The jury is split on best methods. But the sliced tenderloin is nice pan fried, all agree, with simple salt and pepper seasoning, and finished with butter garlic. Those are piled high. There are two vats of slow cooked shredded roast in espagnole, heavy on the tomat. Lamb cutlets are stacked like a glistening forest of meat and bone trees, with rivers of mint jelly running between them.

The crowd of protesters are starving, but still not a one thinks they have the right to eat from the ministers table. They stand politely. Some of the men remove their hats, and all of the women. Children are held close to their knees. A hush covers the room, as if speaking loudly is inappropriate. They feel awkward about the Valkyries, the bass and brass of which can still be heard from so unfortunately close. One thoughtful soul, ashamed to have them now, collects the placards from their keepers. Many regret, lest this symbol of active protest bars them from the succulent delights of the table.

A door opens at the far end of the room. The protesters nearby shuffle to the side, creating an aisle, through which Aoife can approach. She steps up to her end of the table. “Hello everyone, and welcome.” Her voice is studied. She has a confident delivery. Aoife stands straight. The table is high enough for her to put her palms down without bending over. She nudges a few dishes aside with her wrists in order to do so. “This,” Aoife sweeps one arm over the spread, as if revealing a prize on a game show, “is our olive branch to you. People don’t threaten violence in their demonstration unless the grievance is terrible. Most of the time people will tolerate a very lot. And we, here in this building, can see how much you have suffered by your actions here today.”

Their previous passion was only hunger disguised. Most of the protesters feel that hunger now. Aoife knows the power of a half truth. “All this fuss over genetic manipulation we can settle to your satisfaction. There’s nothing too difficult about that. For now, be assured, we’re not in a desperate hurry. Let the egg heads jerk off Murphy and collect his sperm. Let them get sticky with it. Let them try and wash it off their feet. I made him sleep on the sofa for almost a year because he kept staining the sheets.” The crowd has loosened. Shy, blushing smiles pop into giggles. The protesters will not protest against Aoife. They like her. It’s the institution that deserves their wrath, not her. Aoife has them by the ear.

“It’ll be years before your worst nightmares are realized from the research this hospital is conducting now. This building will look into the proper regulations for what they’re doing. Because you are so passionate about the issue, we will update you in a newsletter as to the progress. Here in the Governor’s office, we’re not trying to be underhanded in anyway. I’ve been speaking to the Governor about this for hours. He’s worried sick. This punch come out of nowhere and caught him blindsided. We’re willing to work with the people to get you what you want. I’m sorry it took vigilantism to get us to listen. We’ve heard you now. You’ve opened our ears. Give us a chance.”

Hands rub together, jaws are loose, tongues hang out, and earnest expressions face Aoife, while their feet inch towards the table. Their hands are agonizingly close. Aoife raises a halting hand and pleads, though clearly happy to do so. “Please, wait. This is yours. You can have it. But first I want you to go outside and see what has been prepared for you by the Whites. It’s unfair that they don’t get a chance to compete. Then if you prefer ours to theirs, you’re welcome to everything we have to offer. Let this food represent a renewing of our friendship.”

Time is liquid. We are swept in a current of time through our lives. We may choose to float along, buoyant, without agency, tossed this way way that, sometimes carried by the gentle flow of a broad river, sometimes dashed against rock and root of narrow canyon, according to the whims of fickle fate. Or we may choose to thrash furiously in the churning waters, asserting ourselves against the oppression of her unsympathetic force. Either way, we are propelled forward from the mountains of our birth to the inevitable oceans of our death.

Murphy is a floater. For most of his life, things have happened to him, rather than because of him. But it’s hard to tease the two apart. He has always felt his actions matter, as most people do, and such a perception is a reality for the individual, trapped within the confines of their inescapable, subjective perspective.

Murphy chose to cooperate with the doctors and the hospital. The opportunity cost was immense. Whether that cost was worth the reward is for him alone to decide. He’s pretty happy with the outcome thus far. He hasn’t worked in years, at least not for an income that mattered. The necessary essentials to sustain his life are adequately, even amply, provided for under his contractual agreement. His compensation has even been expanded in return for his signature on ever more restrictive non-disclosure agreements, over time. Murphy has little to worry about so long as he remains in a controlled environment. But he doesn’t.

After the better part of a year of seclusion beyond regular visits to the hospital massage room, Murphy thought he’d prefer to take part in the world, even at the expense of his genetic misfortune. A stubbed toe, or a finger caught in a zipper, not terribly frequent, are acceptable drawbacks he is willing to suffer in order to walk and wear clothes. Murphy chooses to hazard even higher costs still.

For quite some time after emerging from his self imposed isolation, Murphy tested the effects of his deficiency. He would attend sporting events, bet on one side, and record the results of his wins and considerable losses. He would place orders in restaurants and keep track of the spilled coffee, the bugs in his food, or the mishaps of service he would receive. He would book flights, with hospital permission, and statistically evaluate the frequency of cancellations and delays. Murphy has become a statistician of the first order through these, and many other trials he has conducted.

At first they aren’t much noticed. They’re seen in ones and twos, caught in kitchen cellars, or crawling over shoes. The people start to talk about the problems that they make. Just what it is that they should do, what precautions they should take. Some are laying poison out, some are grabbing brooms. Cats are hunting everywhere, in each and every room. It’s not enough, the rats still spread, determined in their doom. A week goes by, their numbers grow, the stored grain’s getting thin. The fields are bare, rats ate it all, no harvest’s coming in. Nothing done can stop the rats, and, much to their chagrin, the town concedes against the rats they simply cannot win.

The young are in a panic. Their screaming fills the air. The old are much more stoic, absorbed in silent prayer. Many carry handkerchiefs to mop a teary face. We’ll not humiliate them in this very special case, for I would be found sobbing, curled up fetal on the ground if these vicious rats in masses came laid siege within my town. Cupboards barren, money spent, the water’s stained and brown. They chew and gnaw and bite and 20 claw, they scratch and make a mess. They’re everywhere and all at once, a growth we can’t suppress. We’re on the brink, we’re at wit’s end, and now I must confess I’m off to drink one with a friend, I do humbly acquiesce.

Jerome the gnome, mayor of Hamelin, sat fat and official, defended by a broad oak mayoral desk. You’ve met once before, so you know what’s in store from this self serving whore. “You lousy, sub intellect, bleating, furred moo! I’m blaming this whole god damn mess upon you! You were cheap and indulgent, you let them begin, and now they’re amok! Tell me, where they’re not in!? An election is coming, just a twelvemonth to go. You’re fired! It’s all on you. Get me re-elected. I’ll find you something new. Now call in those guys that came in from the zoo.”

“You there! You guys go round up these rats. You can use nets, bullets or cats. I don’t care what you do and I won’t ask you why, but those rats have to go or we’re all going to die.”

In runs a man with a worried nervous look. In his hand he holds but one sad lonely chewed up tattered book. “It’s all that’s left! They’ve come and eaten every single page. Our knowledge, lore and custom gained in struggles over ages gone in days. This infestation must be stopped! Or the mayor’s head, off it will be chopped!”

Here comes a girl, a forehead full of furls. So young to be anxious, but she’s trying to be brave. “These rats, my lord! Have no respect, they fill each nook and cave within my home and in the street. They cannot decently behave! I’ve come upon a prayer that the state my soul will save!”

A third shuffles in, this one just a child, “My tummy is empty, I haven’t eaten for a while. No grain, one can’t get fed. Can one of you here spare some bread?”

“Out, child, now! That’s enough of your complaints.” He was pushed out the door and later put into restraints.

“You bastards are staining my triumphant campaign! My career is over and my

secrets out! My guilt and my shame! No! I’ll

not have it. We’re stopping this game. Set

fire to the buildings. We’ll burn the place

down!”, when in pokes the head of a mysterious clown. Or colourful, one might say.

“I’m Piper. I can help, if you’ll pay.”